The World’s Longest Auto Race

Around the World in 80 Days Motor Challenge

In 1908 a group of automotive pioneers set out on the grandest of adventures, and record setting exploits a 22 000 mile race around the world from New York City to Paris France in a machine that had only been invented 23 years earlier. The race, envisioned by a Paris newspaper, was co-sponsored by the New York Times. So daunting was this undertaking that only four national teams in six cars mustered the courage to compete, USA, Germany, Italy, and France. Even Henry Ford doubted it could be done. He was half right as only three cars made it to the finish line.

Only 4 years earlier the 1350 mile race from NYC to St. Louis, Missouri took 18 days and saw 11 of the 77 cars drop out. A year earlier the Paris to Peking race (route actually reversed) took the leader 60 days to complete, while the second place finisher came across the line three weeks later! Nearly any length of race was an endurance race if it wasn’t on a race track, and the adversities faced were rigorous. Racing around the globe was simply ludicrous.

To better understand the challenges, it should be kept in mind that there were no gasoline stations then, no dealerships stocked with parts, in fact really there were no roads. The best you could hope for in most cases was a rutted wagon track. Worse yet, since the 1908 race left NYC in February bound for Alaska that meant encountering snow. As it turns out, a lot of snow. Outside Chicago the teams met with six foot snow drifts that they fought with everything from shovels, to hauling the cars with teams of horses. Eventually the American team took to the plowed railway tracks. Progress was miserably slow, it took them 8 days to travel just 256 miles. The original course had the contestants following dog sled routes and driving across the frozen Bering Strait to Russia. However once in Alaska the leading US team knew immediately that plan would never play out.

Ours was the first car ever seen there, and the inhabitants welcomed us with a band and parade. But the snow was so deep…and a sleigh ride of a few miles…convinced (us) of the impossibility of driving through Alaska. Some drifts were higher than houses…

The organizers agreed and the route was amended. The teams were rerouted to Seattle where a Steamship would take the cars to Russia where the worst was yet to come!

As great a tale as it is, this post is about a different race, though inspired by the 1908 New York to Paris race this one occurred nearly a hundred years later.

Upon picking the Fintail up at the shipping company for the first time, we were met with a few surprises. While most of those will be saved for another time you can probably guess that they weren’t good surprises. There was however one little surprise that was, the previous owner of the Fintail had stashed a copy of A Lap of the Globe in the glove compartment. The subtitle “Behind the wheel of a Vintage Mercedes in the World’s Longest Auto Race” should explain the connection. The book covers the Around the World in 80 Days Motor Challenge that took place in 2000. It was to be the first such race to entirely circumvent the globe returning to its starting point. Despite a strong interest in endurance motoring, rally, and vintage Mercedes, the book sat on the back burner for over a year. Knowing the reality of these types of modern events is probably what turned me off reading the book. Unlike the race of 1908 , today’s events are simply paid excursions for the ultra wealthy. With paved roads, gas stations every 20 miles, a sweep crew of mechanics, and luxury hotels awaiting your scheduled arrival, there is little romance and little to test the merit of man or machine. The blue collar in me simply had no interest in reading about some rich…dudes playing make believe rally.

So what changed my mind? Well the reading list is long and I needed to bang some off, and since the Fintail is in winter development mode, I thought maybe, just maybe the book might have some valuable tidbits buried within. As it turns out, if a vague lead pans out, it just may result in something pretty great, more on that as it pans out. Really though, what probably changed my mind was a brief moment of self realization.

While the greater Frontseat Driving family truly lives the middle class ethos we purport and while we are tentatively cautious of the monetization of the hobby, the truth is wealth is on a sliding scale and to many in this world, heck this country we ARE the wealthy. While others are scraping by like little boys we are still playing cars, but with the real things. What really knocked the chip of my shoulder was reflecting on our own experience this past driving season. Sure enough we spent a fair amount of money to navigate our own cars for a three day ‘rally adventure’ followed by a sweep vehicle offering mechanical support and with (you guessed it) hotels and warm meals awaiting us.

There is no question that we had an exceptionally fun time on that event. And it was clear that that was the general consensus among the other attendees. It was a great, and value filled weekend. Like financial wealth let’s be honest, adventure is on a sliding scale. Breaking down on the side of a cold rainy, two lane, a thousand kilometers isn’t from home life changing. But when it’s on a sparsely populated island, late on Sunday afternoon it is more than an inconvenience. And when it means missing the last ferry to the mainland, well that straight up sucks. While it might not compare to breaking down in the middle of the Sahara, or rolling down a cliff in Siberia, the chances are yours will be the story being told at the water cooler on Monday morning (if you make it to work). So if we ARE ‘rich’ and we DID have an adventure, who am I to say the entrants of the Around the World in 80 Days event didn’t? Perhaps it was time to open my mind – and the cover of the book.

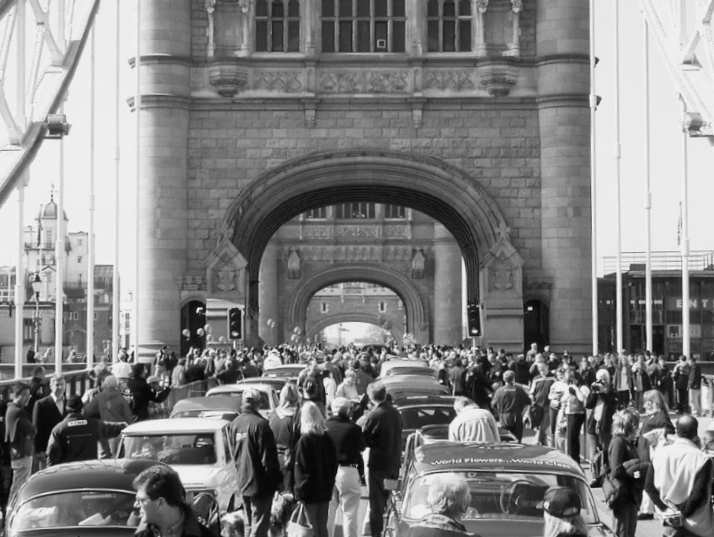

The Around the World in 80 Days event started in London England, travelled through Europe by way of France, Italy, Greece, and into Asia via Turkey. The rally was actually three races in one. The first was London to Istanbul contested by 19 teams. For those continuing on the route crossed Asia visiting Georgia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and across the expanse of China. For nearly half of the remaining contestants Beijing marked the finish line in the London to Beijing Rally, certainly an accomplishment in itself. The remaining 40 contestants had chosen to circumvent the globe. The cars continuing on, travelled by air to Alaska where the contestants picked up the race driving south across Canada via the Yukon, British Columbia, and Alberta. Crossing the northern states back through Canada via Ontario to Niagara Falls, across the border into New York, and New Jersey where again the cars boarded a plane this time bound for Morocco. The final leg of the rally returned to London via Spain and France. The vehicles were restricted to 1968 and older and divided into pre and post war categories. The oldest car to compete was a 1912 Locomobile, the oldest car to successfully circumvent the globe was a 1929 Bentley.

Author Kevin Clemens presents an oddly candid account of the race that is both refreshing and at times awkward as he manages to insult fellow entrants, the organizer (Philip Young), and even his own navigator. While the preface thanks and acknowledges the latter parties, he may have chosen to repeat those kinder words a few times throughout the narrative as confirmation. It was at times hard to shake that uncomfortable feeling like you get when a couple starts arguing at a dinner party. That said the opportunity to see the reality of organizational conflicts, and interpersonal challenges involved in such a long and arduous trek, is rare and welcomed.

Clemens begins the story of this grand event from even before his own involvement starting with its inception in the late 90s. The reader is taken back in time to review the highlights of the rejuvenation of endurance rally sport driven by the three main promoters at the time. This was an interesting and informative aside that helped to illustrate the immensity of the organizational challenges. While Clemens has little to say in favour of the man he does at least point out that while at the time no one in the industry thought he could successfully put together an event of such magnitude, if anyone could, it would have been Philip Young. I found this behind-the-scenes coverage to be especially interesting. In a surprising move Clemens goes on to describe the finances involved.

The first thing we learned was that we would need to have map books, and that they would cost $500. It’s hard to imagine how you could put on a rally with a route book that provides the specific instructions to tell competitors where to go and how to get there, and then turn around and charge them for a set of the necessary maps, but there you are. Next, we learned that a special service to obtain travel visas would be available for a fifty percent surcharge over the usual visa rates. Because you don’t want to be caught going int Azerbaijan with the wrong papers, there wasn’t much of a choice but to pay. Then came the heaviest hit. The two airlifts would cost 5000 pounds sterling. Each. That meant an additional $16 000…A package of hotel rooms (which was mandatory) would be another $8000. Some reached for their checkbooks. Others nodded their heads in resignation. I panicked quietly at my seat…The entry costs to be paid to the organizers now totaled more than $100 000.

The entry fees necessitated financial assistance and Clemens even details his search for sponsorship and how that influenced the make and model of car they raced. In fact in the appendix he even shares how each sponsor contributed. As an aside, considering only the contestants going the entire distance the promoter collected 4 million dollars! Keep that in mind as you read about the hotels, and meals along the way. The book proceeds to describe how Clemens found and settled on his navigator/co-driver and spends a great deal of time describing in detail how the car was modified.

While I really enjoyed the lead up to the race I began to wonder how the book was going to unfold given that at nearly a third of the way through the race hadn’t even started. In some respects I think that concern was justified as the grand adventure was at times reduced to a whirlwind of country names with few details about these exotic locales.

Often that could be explained by the need to cover the teams frequent mechanical problems. A number of times the team is faced with dropping out of the race only to squeak through often by sheer luck alone. Not only was there a need to cover the details of these emergency repairs, but in several cases I think Clemens himself may have missed some of what the countries had to offer as he was spending much of the time wrenching on the car. Often though he sacrificed sightseeing in order to satiate his fierce competitive spirit by going over the car ‘one more time’. While he explains that many approached the race as a grand tour, an adventure vacation, he approached it strictly as a competitive event only taking in the sites or slowing to share a meal with fellow entrants when absolutely nothing else needed being done.

I went to Walmart and bought a jumbo-sized package of adult diapers. I felt a bit embarrassed about buying these and made loud comments in the checkout line about how they were for my grandfather. The reality was , if Mark or I got a bad case of the runs the rally wouldn’t wait for us, and we would have to keep driving.

From what he shares of his fellow competitors and some of their car preparation, we can be fairly certain none of them packed diapers. I found myself terribly curious what Mark Rinkel his navigator thought when he spotted those in the pile of gear. Regardless it shows this was no vacation for Kevin.

All in all the book is a good and quick read, that I believe many fans of automobile racing, rally, touring, or even those like myself that live for the epic road trip will appreciate. However I think too much of the book covers the technical and organizational preparation and too little of the details of the exotic lands visited to interest the reader simply looking for tales of world adventure and travel.

As I began this article with a snippet from the 1908 New York to Paris Race so does Clemens start his book. He returns, delving into the details of the 1908 race several times as past circumstances often paralleled those of the 2001 event. While I had some previous familiarity with the 1908 race the stories and photos were a welcome addition to this book not only as an effective literary device but the stories themselves often contained the drama and romance I felt lacking in his own adventure. While Clemens and Rinkel certainly faced mechanical challenges that nearly ended their race several times, and suffered their own personal hardships, I found it difficult to compare to the gripping details of the great race of 1908. To be fair, it’s tough to compete with stories of teammates drawing pistols and arguing about directions at gunpoint! Clemens himself wrestled with the romance, the point of it all, and even the elitist nature of the event in his closing remarks.

From the outside it’s easy to be cynical about the whole endeavor, Who cares if a bunch of rich elitists drove their pretentious old cars around the world? …Was anyone saved? …it’s hard to see how driving across the (world) had much of a positive impact.

In the modern world, we often have to invent our challenges as Philip Young had done with the Around the World in 80 Days event, but does that make the challenge any less romantic? …I’d wanted the romance, the excitement and adventure, but those things are at odds with the process of daily living.

I won’t give away how Clemens comes to terms with his internal conflict or how he ultimately found meaning in the event. However I will say that his thoughts caused a second moment of personal clarity.

I have often wondered why I get such a kick out of people pointing, staring, and smiling at my vehicles. Mysteriously that feedback seems to be amplified (for drivers and bystanders both) when driving in a convoy of like minded enthusiasts. It’s not the attention, it certainly isn’t status I seek (or I wouldn’t be driving old beaters), yet something is strangely gratifying about the exchange. I think A Lap of the Globe helped me figure it out. Those looks, those reactions are born of wonderment and incredulity. It’s not about inspiring envy, it’s about inspiring someone to follow their dreams and to seek adventure regardless of how romantic, or irrational. Even if the adventure is little more than riding on empty through an unknown countryside. The thought that I might inspire someone to do the same makes me smile.